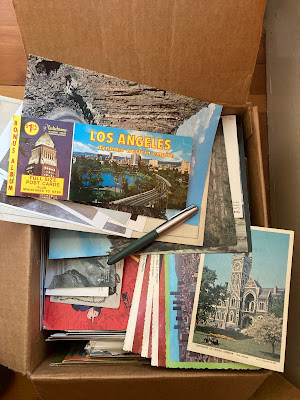

Parental Artifact #25? A box of postcards (used); a box of postcards (blank); and a nice pen.

The internet is full of rabbit holes that one can fall down into and then emerge from hours later, blinking, mouth dry, wondering why it’s dark out. This box of used postcards that got stashed away in my parents’ closet is much the same thing. Bright pictures, short texts that come out of nowhere and are occasionally very revealing or enlightening, or just enough to keep you scrolling on—it’s all there.

There are postcards here over a hundred years old, postcards less than a decade old, postcards my parents sent and received, postcards to and from my grandparents, my great grandparents, work associates, distant family, people I know and people I have never heard of. They are all in a jumble, and making sense of things is a challenge. A card to somebody I’ve never heard of, from somebody else I’ve never heard of, about spring break in San Diego 75 years ago is next to a card my mom sent to my aunt from a vacation twenty years ago. My ability to parse this jumble, how much interest I have in a card, and how much it ads to a character in my memory, is a linear function of how closely related I am to the sender.

I can read little snippets of the relationship between my parents in the cards my dad sent to my mom when he was a young professor away at a conference and she was at home, pregnant with one of my brothers (“REMEMBER TO TAKE YOUR VITAMINS!”—what a biochemist thing to write!). My parents sent lots of postcards to their siblings and parents while they traveled, and often there was the annotation “please save this card,” so they were able to get the cards back as souvenirs. That’s always nice, because I can read my mom or dad’s account of things—even at a posh tourist lodge in Kenya, sweat and flies were annoying, and the kids were rambunctious to the point of concern (sorry, mom).

My grandparents, particularly on my mom’s side, were prodigious postcarders. After they retired, they traveled widely, favoring ocean travel. There were often daily updates, written after a ship-board dinner, as they worked their way up and down the coast of Mexico and beyond. Nothing especially deep—Grandpa was grouchy about a taxi driver, or the market was interesting. There are a couple of cards to and from a great-grandfather on my mom’s side—Christmas greetings, or the complicated business of arranging a meeting while overseas. There are also cards from uncles, aunts, great-uncles and great-aunts, and so on. I did not know them very well, but it is interesting to see what their cards suggest about relationship between them and my parents.

Outside the family, there are a lot of cards between my dad and his various professional associates. Science has long been an international effort so the correspondence was worldwide—former lab mates from Argentina to New Zealand, reprint requests from countries that no longer exist, and lots of cards from my dad and others, away at meetings in the US and abroad, back to their co-workers. And then there are lots of cards about which I have no idea. Maybe they were sent by friends of my grandparents? Still others, I do not recognize the name of either the sender or the recipient—how did these even end up in my parents’ closet? Aside from bits of gossip that are amusing on their own, these don’t really mean much to me.

(I will just note, as an aside, that these cards give lie to the idea that there was a golden age of cursive penmanship. The cards from 1910 are just as illegible as any I write, eccentric spelling is the rule over the entire collection, and micrographia, while great for sending as much information as possible, makes receiving that information difficult.)

There is a larger interest that these cards trigger, less about what was communicated than about how. As Marshall McLuhan noted, the medium is the message. A postcard is necessarily public, open for anyone to read (the Russian word for postcard is “Otkritka” or “open writing”). A postcard is also, despite the efforts of micrographic correspondents, terse. You are lucky to get one solid thought on a card, so they’re not especially deep. They are also, mostly, biased towards being one-way communication. Written on vacation, they can take days or weeks to reach their destination, by which time the sender has moved on to an unknown address so the tone is declarative and replies are rare. All of this sounds sort of like social media, facebook posts or tweets.

However, the resemblance is superficial, the differences bedrock fundamental. Despite being open, postcards are sent to one person (or for my dad’s lab postcards, to a group), and mostly, they are the only ones who see it. While they may not be deep, they do convey meaningful relationship—they are more expensive and time consuming to produce than texts. And while they can be hard to respond to directly, they are more permanent. In my dad’s lab, and in my house, they would get taped to a refrigerator or other surface and stay for years. While I look at these cards sent a hundred years ago, I doubt that any descendent of mine or yours will look at our texts a hundred years from now.

My grandparents had no way to post a photo on facebook, telling a hundred of their friends that they were having a great time in Ensenada but the entertainment was a bit risqué. They would tell the handful of postcard recipients; if they wanted to be more public, they would invite a bunch of folks over for a slide show after returning home. In the next generation, to communicate more broadly, my parents might also include something in their xeroxed end-of-the-year letter. The opportunity provided by social media is truly wonderful, and I try to imagine how my parents would have worked with it, if they could comprehend it. But it is a qualitatively different form of communication. I know that I write differently when I am writing to an individual or small group than when I am writing “publicly.”

So there is the trade—permanence, and a building a more direct personal relationship, in exchange for easily reaching a hundred people to say that the view from the hotel is nice but the food is expensive and made so-and-so sick.

Which brings me to box #2–a lot of blank postcards, and a nice pen. A lot of these cards are souvenirs. Despite writing a lot of postcards, my parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents bought more postcards than they sent, a practice I continue. They are good, cheap, easy-to-carry mementos, especially when cameras were clunky, film was troublesome, and you want a well-produced image of a place. Some of these cards were given away—airlines used to put them in the seat pouches along with the barf bags, and hotels would use them for advertising, and I have a lot of those. Another sizable bunch are of Los Angeles, from when our hometown pharmacy/stationer closed down and they were getting rid of stock. I also have a Parker 51 fountain pen that may have been a graduation gift for my mom, and writing with this pen is a sensuous experience, like getting exactly the right wax on your skis or wearing silk. It seems to me that it would be wrong not to put the cards and pen to use, like leaving a violin unplayed.

So, if I have your address, or if you send me your address, or send me a postcard, I’ll send you a random card (Ok, not totally random—I won’t send the ones my great-grandfather got in the Dutch East Indies, or their like). It will be a postcard, so don’t expect profundity (or legibility), but it will convey my regards, and you can keep it, if you will; the picture will at least be nice or amusing. Maybe you’ll send one back? Maybe in this age of tweets and texts and IM’s, can we resurrect the postcard and the distinctive connection it makes? I’m not going to abandon social media. I mean, this musing IS on social media, I’m not going to print out dozens of copies of it and send them individually to all my friends. But, it is so nice to get something in the mail that isn’t an advertisement or a bill. Why not greetings from a far-flung friend?

No comments:

Post a Comment