Wednesday, September 29, 2010

Bad Science Writing

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

First Day of Class

In class I can do enthusiasm, because I really dig microbiology, but optimism is a challenge.

Monday, September 27, 2010

Monday Musical Offering

But in spite of it all, it's still a nice piece of music. So, enjoy.

Violin Hunting

My career as a violinist (such as it is) pretty much got started thanks to the extraordinary generosity of an uncle, who provided the Real Doctor and me with a rather nice violin. In the spirit of avuncular paying-it-forward, we are trying to further the musical education of various nephews and nieces. As part of this effort, we went violin shopping yesterday. Our goal was to procure a reasonable-sounding 1/16-size violin for our niece.

It’s one of the awful paradoxes of learning the violin that you want the worst possible players—the absolute beginners—on the best possible instrument. A good instrument will teach the student. When the player hits a note ever so slightly off, the instrument will just make a rather dead sound. However, when a note is hit properly, the whole violin will ring. I can tell you from personal experience that that ringing sound is a powerful intoxicant, one that makes you want to keep coming back for more—and so you get better and better at hitting the notes properly, and you become a better violinist. None of this happens on a poor violin. Good notes, bad notes, they all sound the same. So a crummy beginner on a crummy violin will just continue to be crummy.

Because of the laws of physics and engineering (and tradition), it’s really hard to make a 1/16 violin that is at all good. Most do not resonate at all, and sound like a taut wire twanged across the mouth of a tin can. From such instruments, parents expect small children to learn to play the violin.

Our usual stop for all things violin, Ifshin’s in Berkeley, doesn’t sell 1/16 violins, so we went further afield, to Scott Cao in San Jose. Cao’s is an interesting shop, typical in some ways of California. Demographically, everybody in California is a minority, and most people are within one generation of being immigrants. Cao’s shop reflects this; it functions pretty well in English, but is more comfortable in Chinese. This was also true of the customers we saw, with the exception of a Russian who was buying a bow. We tried three different 1/16 fiddles. Two had the tin-can sound typical of a 1/16 fiddle; the (alas, but predictably) more expensive one actually resonated when played, and could produce overtones like a bigger violin. It was also of better “set-up,” which has a dramatic effect on sound. So, that’s the fiddle that will be teaching our niece how to make music.

And how big is a 1/16th violin? It’s not 1/16th the size of a regular violin, but it’s pretty darn tiny:

Friday, September 24, 2010

Friday Fowl

These guys are all descendants of birds introduced to California in the 1800s. Since it's impractical to import a huge number of birds, this population probably has pretty limited genetic diversity and is pretty inbred. It's not too surprising, therefore, that we saw an interesting "sport" the other day on the bike trail--a silver turkey. It's not albino, but it's sort of a gray color like tarnished silver, and it still has all the bars on its feathers. It would be interesting to follow this population for a while, and see how the descendants of this bird turn out.

These guys are all descendants of birds introduced to California in the 1800s. Since it's impractical to import a huge number of birds, this population probably has pretty limited genetic diversity and is pretty inbred. It's not too surprising, therefore, that we saw an interesting "sport" the other day on the bike trail--a silver turkey. It's not albino, but it's sort of a gray color like tarnished silver, and it still has all the bars on its feathers. It would be interesting to follow this population for a while, and see how the descendants of this bird turn out.

Thursday, September 23, 2010

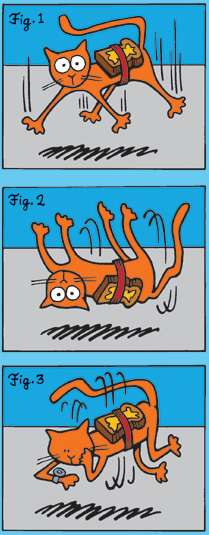

Buttered cats, engineers, and membrane proteins

There’s an old joke about how to make an antigravity machine. See, cats always land on their feet. And, as the Victorian wag James Payn said,

“I’ve never had a piece of toast

particularly long and wide,

but fell upon a sanded floor,

and always on the buttered side.”

So, simply attach a piece of buttered toast to the back of a cat. The toast will want to hit the floor, but it can’t, because the cat’s feet also want to hit the floor. The cat and toast will hover, spinning as butter and paws both strive to make contact—antigravity and perpetual motion to boot!

An engineer would want to play with this, of course. It would be necessary to quantify just how big a piece of toast and how much butter would be required to offset so many grams of cat. One can imagine the white-coated experimenters with clipboards in hand, attaching precisely calibrated toasts to uncooperative moggies. Too much butter, the cat lands on its back. Not enough butter, the cat lands on its paws.

This is almost like an experiment recently described by a group of biochemists from Sweden. These researchers were looking at proteins instead of cats, and how these proteins land in a cell’s membrane. This is actually a significant problem, because many membrane proteins are like turnstiles. You could install a turnstile to only allow people out of a room, or only allow people to enter a room. Similarly, membrane proteins act like one-way gates for the cell, only allowing food in or only allowing toxins out. Getting one of these proteins into the membrane pointing the wrong way would be pretty bad—keeping food out, or importing toxins. The Swedes were looking at a protein in bacterial membranes that allows toxins to go out of the cell, and how it gets oriented the right way.

Going into this, the researchers already knew something about the problem. They knew that the proteins that sit in membranes tend to have more positively charged amino acids facing the inside of the cell than facing the outside of the cell (Proteins are basically long strings of amino acids that fold up into precise shapes; there are twenty different amino acids, some are positively charged, others negative or neutral). They also knew that the proteins needed help getting into the membrane, help that was provided by a group of proteins known as a “translocon,” already sitting in the membrane. What they thought they knew was that the translocon looked at just the first few amino acids in the string that made up the incoming protein, and made it point one way or the other based on that information.

The particular protein the Swedes looked at, called EmrE, was interesting because it was like a cat with just the right amount of buttered toast on its back—half the time it landed in the membrane pointing one way, half of the time pointing the other way. They worked on the assumption that the first few amino acids were important for letting the translocon set the protein’s orientation—so adding an extra very positively charged amino acid arginine at the very beginning of the protein made EmrE point one way, but putting an extra arginine in twenty bases further down the string made EmrE point the other way. So far, the hypothesis that orientation is determined by positively charged amino acids at the beginning of the protein seemed solid.

The biggest danger in research is falling in love with your hypothesis and not challenging it. The Swedes tried to prove themselves wrong by putting positively charged arginine amino acids throughout the EmrE protein. To their surprise (and pleasure, I imagine, since we get a buzz from finding the unknown), they found that it didn’t matter where in the protein the extra arginine was added. It could be at the beginning, the middle, or the end, and the extra arginine would always be facing the inside of the cell. It was as if the EmrE protein were like a cat with the perfectly balanced amount of buttered toast on its back—adding that extra arginine anywhere was like adding an extra little morsel of buttered toast anywhere. It was enough to absolutely determine which side would hit the floor.

Having found a system that was fun to play with, the Swedes played with it. Could the arginine be put at the very end of the protein, rather than the beginning? Yes. Would this still work if the protein were longer? The Swedes made the protein a full 20% longer, and put the positively charged arginine at the very end of the protein—like a cat with a veeeery long tail with toast on the end—and still the protein was oriented in the membrane so that the positively charged arginine faced the inside of the cell. Other amino acids have weaker positive charges than arginine—would they work? Yes, and like arginine they worked anywhere in the protein, just more of them were needed.

This was a bit more than idle play, however. It told us something we didn’t know about how the translocon works. Apparently, it sits in the membrane and accepts an entire protein, rather than just looking at the first bit. Once the whole protein is there, it checks to see which side has the most positive charges, points it in the right direction, and only then inserts it into the membrane. So, the translocon has to be much bigger than we thought—big enough to hold an entire protein. Also, it has to have some source of energy to flip proteins one way or the other—and we don’t have a clue about this energy source. This is also of interest to more than just those who study bacteria; our cells have membranes full of proteins, and those proteins are inserted in the proper orientation by a translocon very similar to the bacterial version. If we know how this machine works, we come closer to the ancient instruction “know thyself.” And, no cats were harmed, or even buttered, in this study.

Susanna Seppälä, Joanna S. Slusky, Pilar Lloris-Garcerá, Mikaela Rapp, Gunnar von Heijne (2010). Control of Membrane Protein Topology by a Single C-Terminal Residue. Science 328, 1698-1700.

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

Trendiness, and a message for Val

So, according to Outside Magazine and Sunset Magazine--who should know--the trendy train that we must all hop on board right now is Stand-Up Paddleboarding. To be really with it, call it "SUP" as in "dude, 'sup dude?" We've seen people doing this down in Pacific Palisades, and up here on the American River.

But wait--if it's in such a lamestream magazine as Sunset, isn't it already passe? Why yes, it is. How is one to stay ahead of the curve? Simple--imitate the guy we saw on the bike trail the other day. He was riding a "longboard" skateboard, propelling himself with a carbon-fiber SUP paddle with the blade sawn off and replaced with a rubber wheel. He was on the bleeding edge of fashion, and by the looks of it, he could soon be just bleeding.

Of course, this trend-conscious young man could just have been trying to keep up with trendsetters such as myself...

Sunday, September 19, 2010

Career paths

I did not know there was such a job. I knew that there were professional food photographers (and food stylists), and the violin building class we took is taught by a guy who got his foot in the door as a violin photographer. But coin photography?

It actually makes sense. Coins are a collectible commodity, and their value is highly dependent upon their appearance. If you would traffic in coins, you need to have fair representations of them. Coins are also (apparently, though I did not know this) the very devil to photograph well. Capturing the nuance of a subtle patina and the shadings of relief are tricky under the best conditions; collectible coins are generally permanently encased in clear plastic, which complicates the project. So, it makes financial sense for a collector to hire a pro. The photographer was quite proud to show us some of his work, which fills his auxiliary hard drives, and it really is quite spectacular. Additionally, he gets paid to travel, and gets to see up close some incredibly valuable specie. As any coin collector will tell you, such items are heavily laden with intriguing history, sometimes almost as much as violins.

The photographer used to work in the financial field. He quit, developed a hobby into a career, and has never been happier. It doesn't pay as well, and he has to hustle, but beyond making an acceptable living what matters is happiness, not extra zeros.

Oh, and how many coin photographers are there in the U.S.? It is rather a niche market. Our coffee-house cohort is one of maybe ten or so nationwide. The field would be crowded by an eleventh, so I don't think I'll follow that particular path.

Friday, September 17, 2010

Tuesday, September 14, 2010

Flyovers

We left, but as we finished our ride, the next few acts were in the air. We got to see a couple of venerable P-38's motoring around, and they were joined by a stupendously loud F-22. I prefer the P-38 on several grounds: aesthetic, with a design based on elipses rather than harsh angles and radar stealth; auditory, as it is not deafening; and something like moral--it was designed for an immediate and honorable need, acquitted itself well, then retired to be hoarded by a few collectors. The F-22, on the other hand, seems to have been mainly built just in case and for the benefit of a bloated military-industrial complex, and hasn't really distinguished itself except in service except in its ability to overshoot budgets.

Later, there was another flyover by what some view as a massive government make-work project. I was walking the dog after dinner, about 8:30 PM, and I saw a phenomenally bright satellite flying overhead, going from west to east instead of the more typical south-north track. It seemed as bright as Venus, but winked out as it orbited westward into the Earth's shadow. A quick check on the web confirmed that I'd seen the International Space Station. Stunning to think of a group of humans in that bright dot.

Monday, September 13, 2010

Monday Musical Offering

Thursday, September 9, 2010

L'Shanah Tovah

Wednesday, September 8, 2010

Adventures in the Archives (II)

This Columbia High Fidelity recording is scientifically designed to play with the highest quality of reproduction on the phonograph of your choice, new or old. If you are the owner of a new stereophonic system, this record will play with even more brilliant true-to-life fidelity. In short, you can purchase this record with no fear of its becoming obsolete in the future.

Well, I suppose. It was state of the art of thirty-odd years, and is still fairly widely playable after fifty years. Still sounds pretty good. Not a bad run for a technology.

The music? Pieces by the American composers Theodore Chanler and Lester Trimble (no, I hadn't really heard of them either).

On the one hand, recordings of these guys are scarce, and scarcity fosters value--so I could buy this LP on the web for $55 plus shipping. On the other hand, the music is OK but obviously hasn't become part of the mainstream and is mostly forgotten--so I could probably sell it for at most the price of the vinyl.

On the one hand, recordings of these guys are scarce, and scarcity fosters value--so I could buy this LP on the web for $55 plus shipping. On the other hand, the music is OK but obviously hasn't become part of the mainstream and is mostly forgotten--so I could probably sell it for at most the price of the vinyl.

The supposed future of higher ed

I wonder how long you have to have lived without seeing an actual, live, clueless freshman before you can believe such blithering nonsense. The memory of how real students operate has to fade, and you have to convince yourself that there's no real difference between teaching twenty students and two thousand. There's a lot of reality you have to forget before the Kool-aid of totally online education tastes good, so I'm guessing it's been at least a decade since the author of this pipedream taught a typical lower-level undergrad class.

There's a ton of problems with education in this state, and the UC and Cal State systems are in deep doo-doo. If we view the problem as a budget problem, what's being proposed here is a solution. If we view the problem as how to provide the same quality education to a growing number of students, I kind of doubt that diluting the teaching pool is the solution.

Tuesday, September 7, 2010

New record set for faintness of praise

The filmmakers also interviewed...Gould’s...teenage sweetheart. She provides one of the film’s more amusing moments: asked if Gould was romantic, she responds with a long pause before answering, “sort of.”

Monday, September 6, 2010

Monday Musical Offering

Anyway, enjoy, as much as possible. The video just got loaded today (Monday), so it may not be available until tonight or tomorrow.

Sunday, September 5, 2010

Adventures in the Archives

I have tons of records in my garage. Well, it seems like tons—a box of vinyl weighs a lot, and a box of shellac 78’s weighs even more. Records are delicate, fussy to play, and despite what the most ardent audiophiles say, don’t offer any significant sonic advantage over digital media. For the last few years, I’ve been working on transcribing everything to computer files, making for many fewer tons of records in my garage. Mostly, this is a good thing. You can go from thick, heavy, fragile 78’s:

(about half an hour of music)

or the vinyl I grew up with:

(about an hour of music)

or a CD, (about one and a third hours of music), to bright shiny digital:

(about one thousand, seven hundred hours of music--and it's only half full).

Transcription takes a while. Records get digitized in real time, and initially make enormous files. Track divisions have to be added by hand (the automatic track finder programs just don’t work all that well), and then annotated as to title, album, artist, and so forth. CDs go a lot faster, and usually automatically incorporate track information. Nonetheless, some curating is required. There’s no general agreement as to whether the composer should be noted as “Schubert,” “Franz Schubert,” “F. Schubert,” “Schubert, Franz (1797-1828)”, or “Schumbert.” For all albums, it’s nice to find some album art—especially for those I bought mainly on the strength of the artwork.

This is a real challenge for an LP that went out of print in the 1970’s (and by the way, that's an excellent recording). For more recent stuff, the automatic systems often fail, requiring more work to get a good picture. So, that little hard drive there represents a significant investment of time, but one that is for the good.

This is all a repeat of earlier history. My granddaddy told me about a friend of his, an audiophile and music lover, who had an extensive collection of 78 rpm albums back in the late 1940’s. The LP was being introduced, and the 78 faced obsolescence. Rather than discard his collection, my granddaddy’s friend resolved to record his albums for posterity. At the time, there were two options. One was magnetic tape—a brand new invention, with bugs to be worked out, and generally regarded as having terrible fidelity. The other was wire recording. Wire recording works on the same principles as tape recording, but the magnetic signal is stored on a stainless steel wire finer than a hair. At the time, it was a tried-and-true technology, having been around for decades and extensively refined during the war. A wire recorder cost a lot then, a couple of thousand in today’s money, but it was state of the art:

So, at the time, wire recording was the obvious choice. He transferred his entire collection to wire and threw out the 78’s. There’s an irony to this story; he sort of made the right decision, as wire recordings are extremely durable, while magnetic tape crumbles to iron oxide dust after just a couple decades.

Sad to say, I don’t know the end of this story—whether my granddaddy’s friend was happy with his wire recordings, or whether he was driven to despair by their almost immediate uselessness. However, I can almost identify with his tragedy. I’ve spent a huge amount of time recording CDs and LPs to digital storage and curating the collection. We don’t have a lot of space here, so most LPs get tossed or donated to sales as soon as they are recorded. I’m not a total fool, though, so I stored the data on an external hard drive (an Apple Time Machine) and on a back up hard drive (a LaCie; storing the collection on an external drive was necessary as it was big enough to cause my computer to grow constipated).

Our house has a funky electrical system. Like a diseased brain, it suffers periodic blackouts, and the current seems to run unsteadily. It is unable to charge certain rechargeable batteries, and routinely kills 15-year fluorescent light bulbs after a year. Our electrical gremlins killed our back-up hard drive (which, being a back up, we didn’t check all that often, so we didn't notice it when it occurred) and then killed our Time Machine.

I was distressed and distraught. I couldn’t help but think of the things that were lost. But fortunately, help was at hand. B.D., the computer guy in Duva’s department, generously agreed to try to recover the data. The hard drive was totaled by a head crash. However, the Time Machine seemed only to suffer from some sort of programming difficulty—“misjigulation of the frangigating defumitors,” I think B.D. said, but he has a bit of an accent so I may have misunderstood. He set to work on it.

I’m sure that nobody really knows how computers work. There’s a saying attributed to Einstein that insanity is doing the same thing twice and expecting different results. B.D. tried the same time-consuming thing once, and the hard drive didn’t respond. He tried it twice, and it still didn’t respond. He tried it three times, four times, with no results, and called me up to give me the bad news, and I thanked him for his efforts and drove over to pick up the catatonic device. When I got there, B.D. greeted me with a big smile. He had tried the same thing one more time, and it worked. The entire thing was good as new—almost all sixteen hundred hours of music. I have been experiencing a marvelous feeling of relief ever since.

We’ve got stuff triply-backed up now, everything is surge-and-pulse-and-otherwise protected. I am thinking of leaving back-up hard drives at different locations in event of fire or meteorite impact. I still have the last big box of LP's to transcribe, but I think we are set until the next technology comes along. Of course, there’s all my slides that need to be scanned because I don't have a projector any more. And all these books--they take up lots of space, and I can read 'em on an iPad. They need digitizing...

Saturday, September 4, 2010

We have a winner!

We went through four rounds of trial bows--and round trips to Ifshin's and back. There was never a bow that jumped out in front of all the others; however, this bow was always the best of the lot. The more we played it, the more we liked it; the last time we went to Ifshin's, we tried a whole bunch more bows (including a very nice one by Monique Poullot), but again, we kept coming back to this. In romantic comedy terms, we didn't fall in love with this bow at first sight. This bow was the reliable best friend who was there through thick and thin, and who we came to realize was actually the one we should have been been with all the time.

We went through four rounds of trial bows--and round trips to Ifshin's and back. There was never a bow that jumped out in front of all the others; however, this bow was always the best of the lot. The more we played it, the more we liked it; the last time we went to Ifshin's, we tried a whole bunch more bows (including a very nice one by Monique Poullot), but again, we kept coming back to this. In romantic comedy terms, we didn't fall in love with this bow at first sight. This bow was the reliable best friend who was there through thick and thin, and who we came to realize was actually the one we should have been been with all the time.Of course, life isn't a romantic comedy. I'm sure Duva would drop this fine bow in a flash if somebody offered her a nice Peccatte or Tourte.