Parental artifact #15–a book, and a complicated relationship with religion

Religion was as formative in my upbringing as the weather on Neptune. I went to a preschool run by the local Presbyterian Church, but that’s because it was the preschool within walking distance. My parents were married in a church, but I don’t know why or whose decision it was. When we visited my mom’s parents or brother, no graces were said, no bibles were read, and if Jesus Christ was mentioned, he was on a crutch. If you go back far enough, you’d find WASPs and maybe a Lutheran or two on that side of the family, but you would have to dig for evidence of piety. On my dad’s side, his mom’s family was Irish Catholic, but there’s no evidence that it was at all important in her life. My dad’s dad, on the other hand, had a more interesting story. While he was not in any way observant or overtly religious during my life, religion was an inescapable part of his biography.

My grandfather was a refugee from a Jewish community in the Pale of Settlement in modern-day Belarus. He was also a refugee from Judaism, as practiced where he grew up. He described his education in the old country without fondness. Rote learning and memorization of texts was dull, and hunching over books in dim conditions contributed to health issues later in life. It was not useless; on arrival in the new world and the prairies of Canada, he was able to use this education, teaching Quakers who wanted to read the Torah in Hebrew. However, within a few years, he was in college and soaking up a vast amount of secular philosophy.

I am speculating about the psychology behind the events of a hundred years ago and a person I only knew as an old man, but I feel that he delighted seeing other approaches to the big questions, and his philosophical world expanded along with his geographical world. His personal life further separated him from his religious upbringing when he fell in love with my grandmother. From a very few letters I’ve seen, this was an event of oceanic proportions in his life, and it led him further into Western philosophy to find beliefs that better explained his world. It also strained his familial relations. There was a wall growing between him and his religious past; he was building it up from one side, his family from the other.

But any refugee will have some warm memories of the land they fled, however urgent their departure. Matzoh show this well (It’s Pesach as I write this, perhaps the most education-centered holiday in any religion, in which every component of the observation seems to have instructional purpose. So, it is appropriate that matzoh are the prompt for this). I remember my grandaddy telling little me about matzoh. He told me about sourdough, and the work of maintaining it, and how people would always save a little for the future. He told me about how the Jews of Egypt had to flee before their bread could rise, symbolically giving up a certain future to become refugees. Then, getting wistful, he spoke warmly of the communal effort of the Jews of his town to prepare the bakery and make Passover matzoh. He reminisced further, clearly relishing the memory of the taste of pure, essential wheat. As he munched on some store-bought egg matzoh, he told me how nothing since has compared to that.

He also noted, gesturing with an egg matzoh, that he was going to hell for this. It was Passover when he told me this, and he noted that he was in good health and should get no dispensation to eat anything other than plain matzoh for Passover. The people he grew up with thought that amounted to a grave wrong; he thought they were silly, even insulting. He wasn’t angry, so much as he was dismissive.

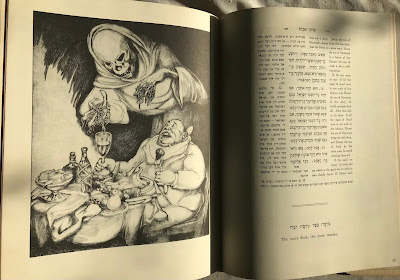

Like matzoh, this book is another fragment of his past life that he held dear in spite of the troubled history. Beyond the stories behind matzoh and hamantaschen, he hardly ever talked to me about the religion of his youth—except this book. He would sometimes mention it, or quote from it, and this particular volume was the only book from the Jewish tradition that he ever pointed me towards. The Pirke Avot, or “Wisdom of the Fathers,” is basically a book of sayings or proverbs that is tucked into the Mishneh (an encyclopedia of Jewish case law that elucidates the application of the Torah’s commandments). While a share of the wisdom in this book emphasizes study of Torah, most of it is straightforward humanist truth, presented in plain but eloquent language. On avoiding excess: “The more flesh—the more worms.” On the need to do right: “It is not your lot to complete the work; nor is it yours to desist from it.” A seventy-five year old man could find many opportunities to drop these nuggets of truth on an eight year old grandkid, even if he were trying to free himself from the chains of his past religion.

Today, here am I, _hineni_, a Jew. The religion I adopted (and that adopted me) in the late 20th century, is different from the religion my granddad fled, as practiced in the late 19th century. G_d has seen much since then: industrial war, the triumph of science, the Shoah, the overwhelming interconnectedness of the entire world, the threat of humanity’s suicide from nuclear weapons and climate change. It seems that all religions have some statement that they are eternal and unchanging, but this is advertising copy. Having studied biology all my days, I am used to seeing the evolution, succession, and extinction of organisms, while genes persist—and even genes evolve and change. The organism of Judaism has evolved. This book, the Pirke Avot, is one of its genes that I inherited, along with my Y chromosome, from my granddad.

My practice is different from that of my grandfather’s youth, and the way I read this book is different. It is definitely shallower and less all-encompassing: language is a hurdle I have not overcome, and there are references that do not resonate for me. But it is like music: one can find deep meaning in a Mahler symphony without understanding German poetry or harmonic theory. I read the Pirke and I am still moved, but differently from my grandfather, and in a different world. Our Passover seder still features matzoh ball soup and haroset, but it’s Tom Kha Matzoh Ball and a chunky guacamole.

I don’t think it’s possible to go back to the faith of my grandfather’s youth. My experience of the Divine is far less literal. The Divine’s expectations of me are perhaps different, and what I seek from prayer to It is far less of a physical nature. Manifestations and miracles do not feature significantly in my religion.

And yet…

There is a discordant and disturbing moment towards the end of the Passover seder. After hours of festivity, welcoming strangers, remembering our peoples’ suffering and celebrating deliverance, we rise, open the front door, and look for the prophet Elijah, whose appearance would be a harbinger of the world’s redemption in this age. With this hope-filled gesture, we ask of the Divine,

“Pour out Your wrath upon the nations that do not recognize You,

And upon the kingdoms that do not call upon Your name…

Pour out Your wrath upon them, and let Your burning wrath overtake them.

Pursue them with anger and destroy them beneath the heavens of the Lord.”

This is a difficult piece of the ritual, and its violence always disturbed me. These lines refer to Amalek, whose sin wasn’t apostasy, but that he preyed upon the weak and defenseless, the ones struggling to keep up with the caravan—in modern terms, those whom society is leaving behind. Perhaps we’re admitting that redemption cannot be universal, that there are those so dedicated to evil that the liberation of the world demands their destruction.

Lately the world seems to have turned into a darker and crueler place. Governments have been seized by aspiring autocrats who lust for power and relish cruelty. Demagogues have whipped up fears and violence against people who simply want equality. Oligarchs grow obscenely rich, pulling on the levers of power to accumulate megayachts and spaceships while greasing the skids for others to fall into poverty. Religious zealots work with all of them to enforce an unjust, rigid, and bigoted culture. So much of society seems to be racing to become Amalek, plundering and killing the already weak and defenseless.

These last few years, we have reached this part of the seder, something really uncomfortable happens to me—something that my grandfather rejected, and that I strongly dislike in myself. It comes from a place of exhaustion and diminishing hope. I find myself on the first night of Pesach, standing at my door in a midnight darkness that is as metaphorical as it is literal, actually searching, earnestly and honestly, for Elijah. I am looking hard for the old man, and staring into the dark for that sign that the Divine, with a certain amount of wrath, will reach into the world and make it whole and we will know Shalom.

Next year in Peace!

No comments:

Post a Comment